Here's Dr. Helen's third instalment in our genetics series, and this time we are starting to see tangible results. Thanks again to Helen, Ilze and all the folks at the genetics department at Aberystwyth University for doing all this work for us. We couldn't get any funding for it so they decided to do it for free. I will write a follow-up blog next weekend, but for now, here's Dr Helen to explain the results we've received during the last few days.

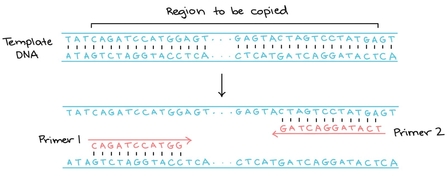

In my previous blog, I mentioned the lab technique that's crucial for all the genetic analysis that we're carrying out on our osprey DNA samples: the polymerase chain reaction (PCR for short). It's a way of turning a tiny quantity of DNA into an amount that's sufficient to work with.

At the same time it ensures that you're only looking at the right part of the DNA from the species you're interested in - in our case, ospreys, of course - rather than contaminating DNA from other plant and animal material. As I said last time, there could be DNA from all kinds of things in an osprey's mouth!

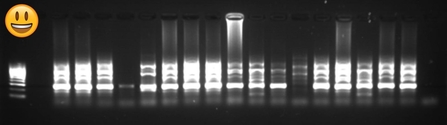

Clarach's saliva - there's more than just osprey DNA in there