This article is reproduced from the Dyfi Osprey Project's Facebook series 'Seven Things You Never Knew About Ospreys' that ran June 3rd - June 9th, 2013.

Seven Things You Never Knew About Ospreys

Part 1 - Populations and Distribution

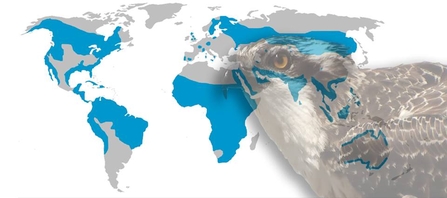

Despite being rare in the UK due to centuries of persecution, the osprey is one of the most widely distributed raptor species, second only to the peregrine falcon. You will find ospreys on every continent on earth except Antarctica. They are superbly adapted to living and breeding in extreme environments from the freezing cold temperatures of the Arctic circle to scorching hot equatorial temperatures.

Ospreys are not closely related to other birds of prey, having had no common ancestor to another bird species for at least 15 million years. That's twice as long as when humans and chimpanzees both shared an ancestor.

Despite their huge global range and millions of years as a single lineage, ospreys look pretty much the same the world over. Some are shorter, some are paler, but the overall template of what an osprey looks like has remained unchanged for millions of years. There are four main 'sub-species' of osprey recognised based on where they breed.

1. Pandion Haliaetus Haliaetus - Palearctic: Europe all the way to eastern Russia (to the left and above Ceulan's head on the map below). Most of these migrate directly south during the non-breeding winter although some small populations that breed in sufficiently hot countries are non-migratory; those ospreys that breed around the Red Sea, for example.

2. Pandion Haliaetus Carolinensis - North America: Tends to have larger, darker body and a paler breast and head than 1. These too migrate south in the winter but some birds breeding in hotter areas like Florida, California, and Mexico will stay put all year round.

3. Pandion Haliaetus Ridgwayi - Caribbean Islands: Very pale head and breast compared with 1, and only a weak 'eye mask'. These do not migrate.

4. Pandion Haliaetus Cristatus - Australia and Tasmania: These do not migrate and some people consider these to be different enough from other osprey populations to be a separate species (Eastern Osprey).

The worldwide population of osprey is very difficult to estimate but is in the many tens of thousands of individuals. In the UK, however, there are only around 260 pairs - around half the population of golden eagles. Like the eagle, most of the ospreys are in Scotland with just a handful of pairs in England and Wales (around 10) and none in Ireland.

World osprey distribution