Richard Page, an ocean campaigner for Greenpeace International, contacted me a few weeks ago. He had a couple of months off planned and was thinking of going over to west Africa for a spot of birding. Not only that, he was wondering if he could be of any use in trying to find any of the 2011 Dyfi tracked ospreys!

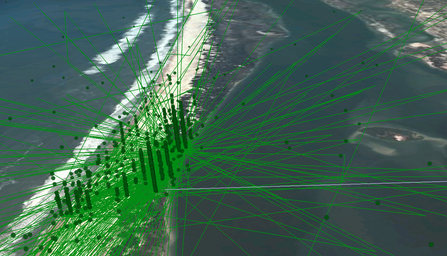

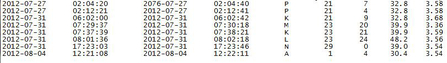

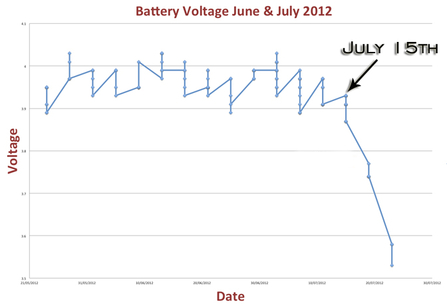

I explained to Richard the situation regarding Einion and passed to him Einion's last coordinates, including the general area he had been in since mid February. Einion's last GPS location point was sent back to us on July 22nd at 14:00. He had been at this same general location on a beach 13 miles south of St Louis for just over five months.