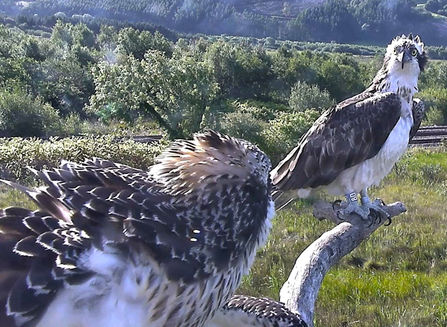

Aeron returned to his natal nest as an adult this week.

Brother to two sisters in 2017, Menai and Eitha, Aeron like many of his brothers before him was a fairly independent chap.

Here he is on his first ever flight on 11th July 2017 as he almost crashes into his Dad, trying to land besides him.